Nearly 23 years ago, Eran Moshe—a veteran nurse at Israel’s Hillel Yaffe Medical Center—realized something was radically wrong with him. At the time, he was working both in the hospital’s operating room as well as checking in on elderly patients.

“I started to have trouble breathing,” he said at the 15th International Conference on Myasthenia and Related Disorders in The Hague, Netherlands. “I was 37 when the symptoms began — shortness of breath, tingling on my left side and face. It sounded like a stroke, but it wasn’t. Then one day I visited my parents. I had to climb three floors and for me it was usually easy, but suddenly I felt like I was having a heart attack.”

Moshe went straight to the hospital, where he was given a CT scan, an electrocardiogram (EKG) and a heart catheterization. Everything checked out fine. But since he was a nurse and knew the system from the inside, the chief anesthesiologist confided to Moshe that he believed the culprit was myasthenia gravis (MG).

“He said I had all the signs and told me to go to a neurologist. But the neurologist said it was just anxiety,” he recalled. Eventually, Moshe was admitted to Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (commonly referred to as Ichilov Hospital) and in 2005 was diagnosed with MG. A neuromuscular specialist there put him on 80 mg of prednisone a day, given that he weighed 80 kg at the time and the protocol is 1 mg/kg of body weight.

But the steroids pushed his weight up to 130 kg, said Moshe. He tried plasmapheresis, or plasma exchange, as well as intravenous immunoglobulin — neither of which was effective. Then he took an immunosuppressant, mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). This worked for about half a year.

“Finally, I was put on rituximab and this stopped progression of the disease. For 12 years I took rituximab and could begin living again,” said Moshe, who has used a wheelchair since 2012. He’s been with Sofia, his caregiver and life partner, for 27 years. “She’s a nurse too, so I can trust her.”

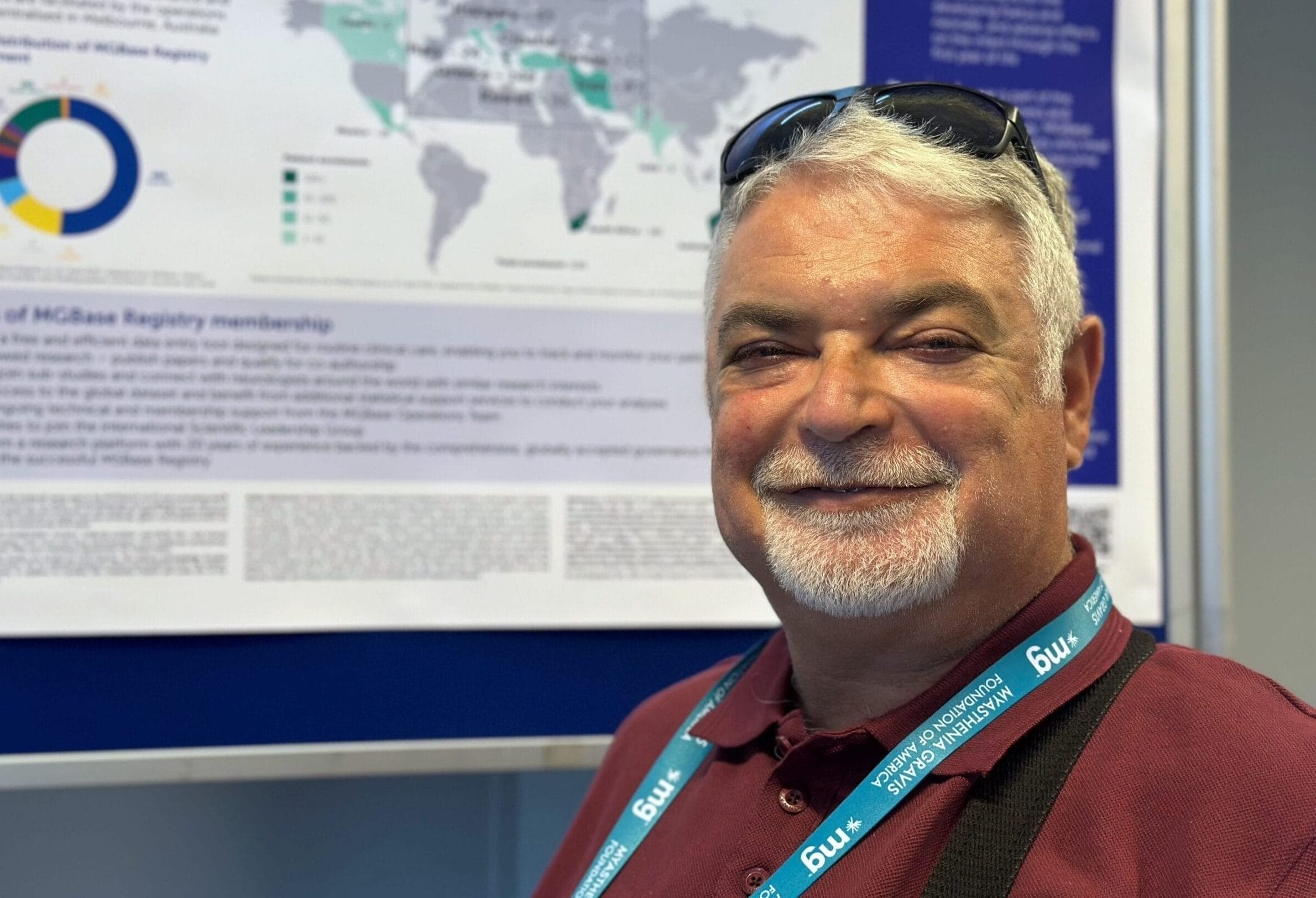

Moshe, 60, is CEO of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of Israel. Based in the Mediterranean coastal city of Hadera where he lives, the foundation has about 900 members, though Moshe estimates that Israel — with a population of 10 million — is home to 2,500 people with MG.

Despite its political and security challenges, Israel is emerging as a leader in MG research, with basic science and clinical trials now being done not only at Hillel Yaffe in Hadera, but also Rambam Medical Center in Haifa; Rabin Medical Center in Petah Tikva; Ichilov in Tel Aviv; Soroka Medical Center in Beersheva; and Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

“Israel is a medical hub with very strong hospitals, strong medical schools and a very vibrant scientific community,” said Dr. Kfir Oved, the founder and CEO of Canopy Biotech in the northern town of Yokne’am. “Myasthenia gravis is a very interesting autoimmune disease in the sense that we find similar prevalence rates across the world, Israel included.”

Garrick Hoichman is a medical student and research assistant to Dr. Adi Vaknin-Dembinsky, a neurologist at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

“We are working on finding potential biomarkers for MG — specifically soluble biomarkers — that could predict the course of the disease,” he said. “We also have this international research we’re conducting with France and Italy, which aims to find personalized immunosuppressive therapy for MG patients using AI, and of course finding potential biomarkers as well.”

The impact of stress on patients with MG

The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of Israel has its roots in a closed Facebook group Moshe launched 13 years ago. In 2020, he and two other patients formed their nonprofit, which today has about 900 members. Most are Jews, though some Israeli Arabs and Druze also belong, as well as ultra-Orthodox Jews who don’t use Facebook.

Linoy Arbel runs the foundation’s WhatsApp group for women, which comprise about 60% of Israel’s MG patient population. Arbel, who lives in Harish — a small city south of Haifa — was diagnosed with MG just over eight years ago.

“My symptoms are more in my speaking. I used to speak faster and more clearly. Now I need to struggle to pronounce each letter,” said Arbel, 36. “I have two kids, 13 and 10, and they look out for each other because I can’t do housework — not laundry, not cooking, not cleaning.” In addition, when Arbel is extremely tired, her eyesight becomes blurry and she sometimes sees double.

The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of Israel holds annual conferences that attract about 100 people. By coincidence, the 2025 meetup was to take place in Tel Aviv on Jun. 13 — the same day Israel launched a pre-dawn strike against Iran’s nuclear weapons program, sparking a war that forced nearly the entire Israeli population into safe rooms and bomb shelters. (The event has since been rescheduled.)

That kind of stress is extremely damaging for an already vulnerable MG patient population, said Moshe. He’s among the 15% of Israeli MG patients who are seronegative, meaning people who lack detectable antibodies in their blood yet still experience symptoms of the disease.

“When you are in stress, your immune system gets weak. I take a lot of corticosteroids, and in myasthenia, if you take a big amount of corticosteroids quickly, it can cause a crisis. And if you reduce it too quickly, that can also cause a crisis,” he said, adding that under normal circumstances, it takes a year to reduce the dosage from 20 mg to zero.

Added Hoichman: “Stress is a key factor in MG as well as other autoimmune diseases. On a basic level, it’s much more difficult to receive treatment during a war. Some patients need to take mestinone, a home treatment, and other patients in Israel rely on getting their treatment in the hospital, and I think the war has made things much more difficult for them.”

During Israel’s 12-day conflict with Iran, Moshe — like many other people with MG — slept overnight in a concrete-reinforced safe room because he isn’t able to wake up, dress and get to a nearby underground bomb shelter at a moment’s notice. Many patients with MG also require oxygen or breathing machines, complicating their situation.

Sadly, one of the hospitals conducting MG research in Israel — Soroka Medical Center in Beersheva — sustained extensive damage during an Iranian missile strike on the war’s seventh day. Yet nobody died or suffered serious injuries, largely because the surgical wing, which was destroyed, had been evacuated to underground facilities the previous day as a precaution.

Sign up here to get the latest news, perspectives, and information about MG sent directly to your inbox. Registration is free and only takes a minute.